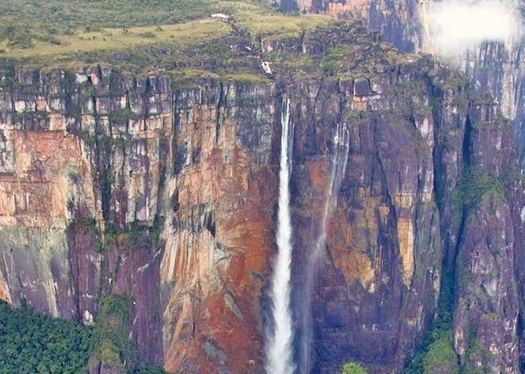

Salto del Ángel, in Canaima National Park (Photo courtesy of Inparques)

In March of 2017 Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro established what on paper is one of the world’s largest national parks to honor his predecessor as president, the late Hugo Chávez. Created by executive decree, the park ostensibly protects 7.5-million hectares (18.5 million acres) in Caura, a region in the southern states of Bolívar and Amazonas that is home to indigenous communities and vast tracts of moist forest and savanna.

The launch of Caura National Park came as a surprise. That’s because in the 18 years of Venezuela’s so-called Bolivarian Revolution—beginning in 1999 with populist leader Chávez’s ascension to power and continuing under Maduro after Chávez’s death in 2013—no new national parks had been established.

Since then, there has been little evidence of active conservation in Caura or elsewhere in Venezuela’s once-celebrated system of more than 100 protected areas, including 45 national parks. Indeed, Caura National Park finds itself in a vulnerable state all too common among the country’s officially designated natural lands.

“Caura is a park on paper only,” says biologist Jorge Naveda, who served for three decades in Inparques, Venezuela’s national parks agency. “It has no program of protection and no [enforcement] personnel.”

Due largely to Venezuela’s ongoing economic and social crisis, protected areas nationwide are sorely lacking in personnel and funding. As a result, illegal mining, logging, hunting, fishing and farming have proliferated on conservation lands where in theory only activities such as tourism, recreation, educational programming and scientific research are permitted.

High-profile examples besides Caura abound. Vilisa Morón, a biologist and president of the Venezuelan Society of Ecology (SVE), cites the example of Canaima National Park, a Unesco World Heritage Site known for its table-top mountains, called tepuis, and for Angel Falls, the world’s tallest waterfall. Though the park encompasses three million hectares (7.4 million acres), Morón says its staff numbers just seven and has no vehicles.

Canaima became the focus of controversy in February, when images were circulated on social media showing an elaborate party thrown at the park by an affluent entrepreneur with close government ties. Environmental groups reacted with outrage, arguing that there had been no attempt to address the environmental impacts of the party, for which many guests arrived by helicopter.

The SVE, a network of environmental scientists, researchers and academics in Venezuela, issued a statement in February accusing the government of standing by as protected areas are overcome by ostensibly prohibited activities. These, it asserts, include wildcat mining, the cutting of canal routes through coastal mangrove stands and deforestation carried out in connection with agricultural expansion and the black-market timber trade.

Asked by EcoAméricas for the government’s response, Hilda Ángel Bencomo, general sectoral director of Inparques, called the SVE statement “political.” Bencomo declined to discuss the subject further, however, saying that she did not have government authorization to do so and that her agency had decided not to respond to the SVE’s criticisms through the media.

For her part, Morón notes that illegal cutting in parks is also being carried out by rural dwellers looking to grow subsistence crops and procure wood for cooking fuel as they struggle to navigate the country’s decade-long socioeconomic crisis. That crisis has prompted nearly six million people to flee the country since 2014, causing the biggest migration emergency of its kind in recent Latin American history, according to the United Nations. The UN reports the rate of such departures has been rising so far this year.

Venezuela once was at the vanguard of natural-lands protection in Latin America. Beginning in 1958, when the oil-rich country transitioned to democracy, government modernization spawned policies emphasizing natural resource protection, particularly of watersheds, says Edgard Yerena, a biologist and protected-areas-management specialist at Simón Bolívar University in Caracas.

Yerena notes that Venezuela in 1976 became the first Latin American country to establish an environment ministry. From 1958 to 1993, the number of Venezuelan national parks rose from two to 43, covering 15% of the national territory. Says Yerena: “Venezuela has a notable trajectory when it comes to the establishment of national parks, not only relative to South America but also to the rest of the world.”

Flush with oil revenues and presiding over strong economic growth, the government felt no need to overexploit natural resources. The spectacular expansion of parkland stopped under the second presidency of Rafael Caldera, during 1994-99, and did not resume with Hugo Chávez’s rise to power in 1999.

In part, the end of the trend and the growing government indifference to conservation could be attributed to the budgetary consequences of economic failure under Chávez and Maduro. But experts also cite the outlook and culture of the Chávez and Maduro regimes.

Chávez often viewed environmental policies as an economic obstacle, so he removed resources from that budgetary area, experts say. To aggravate matters, environmental research and technical staff were expected to demonstrate that they supported the government to stay in their posts.

“At the beginning of the Chavista era, national parks were portrayed as too restrictive,” says Yerena. “[The Chávez regime thought] they needed to be opened to development projects and were wedded to a capitalist view of the relationship between nature and humans,” says Yerena. “The government said the idea of the Bolivarian Revolution was different, but never explained what it was. Today, what used to be the Environment Ministry is the Ministry of Popular Power for Ecosocialism, and it’s an empty shell that has neither a budget nor policies. This has allowed a mining boom throughout the country and an increase in deforestation. It is difficult to measure these phenomena, though, because no figure given out by the government can be trusted.”

Naveda, a biologist and former Inparques official, agrees that the current plight of the national parks, and of Venezuelan environmental protection generally, is due in no small part to Chávez’s failure to appreciate the importance of natural resource conservation.

“Chávez visited the national parks and said that farmers should be working there,” Naveda says. “Many people tried to explain to him what environmental conservation is about, but he didn’t understand it. He thought national parks were worthless badlands. In his military mindset, all land had to be occupied.”

Green advocates worry about the state of the entire protected areas system, but they highlight several cases in particular.

Among these is Los Roques Archipelago National Park, a stunning collection of Caribbean white-sand islands and reefs where environmentalists say the government is allowing mangrove destruction associated with the construction of high-end tourism development.

Another is El Ávila National Park (officially named Waraira Repano), a mountainous 80,000-hectare (198,000-acre) reserve just north of Caracas where the government plans to build what Maduro has described as a “socialist commune.”

“Maduro didn’t explain what the project involves, but it worries us because it’s certain to mean construction of housing in the park, which in turn will mean more pressure and pollution for natural systems,” says Alejandro Luy, director of Tierra Viva Foundation, a Venezuelan green group.

Luy asserts that the lack of information on this and a wide range of other environmental matters is deliberate.

“The websites of the Ministry of Ecosocialism and Inparques are completely lacking in relevant data,” he says. “There’s no information on the protected areas budget. There’s no official information on deforestation rates. Nor do we know how big an area is affected when there’s an oil spill. Of course the opacity is intentional.”

In 2016, Maduro announced he would implement an initiative Chávez had announced five years earlier: to spur mining projects across an enormous swath of land south of the Orinoco River. Establishing the “National Orinoco Mining Arc Strategic Development Zone” by decree, he earmarked 12 million hectares (29.7 million acres) for mining that the government says could yield US$1.2 trillion in gold, coltan, diamond, nickel, bauxite and other minerals underlying the area.

The initiative has been intended to provide Venezuela an alternative to oil development. But it has been hobbled by mismanagement under Chávez and Maduro, and by the challenge of marshaling the considerable capital and expertise needed to extract and refine the country’s extra-heavy crude.

So far the Mining Arc has attracted virtually none of the international participation touted by Maduro, with investors reportedly put off by Venezuela’s economic and social crisis and high levels of corruption. Black market mining operations have happily filled the void, and with little apparent obstruction by the government.

“With the government’s expectations unfulfilled, the Mining Arc became a free-ride policy that allowed informal mining in the south of the country without any degree of environmental or fiscal control or regulation,” says SOS Orinoco, a Venezuelan nonprofit that researches environmental conditions in the south of the country. “And there are no geographical limits. The mining extends throughout the entire south of the country, affecting protected areas such as national parks and indigenous territories.”

Beyond the arc

Though officially excluded from the Mining Arc, the three national parks south of the Orinoco—Cerro Yapacana, Parima-Tapirapecó and Canaima—have all experienced mining incursions, experts say.

“The mining dynamic is extending to the national parks, and the environmental cost there is very high,” says Elides Sulbarán, a forest engineer who worked in Inparques for 30 years. “That’s because the soils are poor, which means that when the forest or vegetation is cleared, they take an extremely long time to recover.”

Sulbarán points in particular to iconic Canaima National Park, a longstanding tourist magnet until Venezuela’s economic and political crisis, later compounded by the Covid-19 pandemic, depressed international visitor traffic to the country.

“The Pemón indigenous community, which lives in Canaima, lived on tourism but now many are involved in mining because the soils don’t support agriculture,” says Sulbarán, who during six of his years at Inparques oversaw Sierra de la Culata, a national park in the Venezuelan Andes.

According to an SOS Orinoco analysis based on satellite images, mining operations have caused the clearing of an average 3,600 hectares (8,900 acres) of forest annually in Canaima Park since 2016.

Against this backdrop, many experts believe Maduro’s 2017 decision to create Caura National Park was intended to dampen criticism of the Orinoco Mining Arc initiative.

“I would say he created Caura to buy the support of a portion of the scientific community taking part in the [national] conversation about the environment,” says Naveda. “At the same time, the government is hoping there will be silent tolerance of the ecosystem destruction occurring in the lower Orinoco watershed as a result of deforestation, soil removal, sedimentation and mercury or cyanide pollution caused by mining.”

Bucking the trend

Despite the dour context, however, there have been bright spots, some provided by Venezuelan conservation scientists and volunteers who, against all odds, have kept natural resource protection efforts alive. (See "Pandemic does not deter nest-site ‘eco-guardians’" —EcoAméricas, April 2021; and "Venezuelan crisis doesn’t deter these four" —EcoAméricas, August 2021.)

A larger-scale exception has occurred as well: the creation in 2021 of Venezuela’s 45th national park. Though just the second national park created during the 23-year-old Bolivarian Revolution, José Gregorio Hernández National Park—unlike the creation of Caura National Park—reflects the more deliberate conservation efforts of earlier years.

The 55,000-hectare (136,000-acre) park extends a corridor of protected lands assembled in the Venezuelan Andes since the early 1990s, primarily to conserve habitat of the spectacled bear (Tremarctos ornatus). The South American bear, listed as vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), is considered an “umbrella species,” whose protection will indirectly benefit numerous other species in the ecosystem.

The so-called biological corridor initiative grew out of research done by Edgard Yerena in the late 1980s and early 1990s while working in the planning division of Venezuela’s environment ministry. “The government listened to a professional team and put an idea into practice by creating a park,” Yerena says. “This hasn’t been common in Venezuela lately.”

- Daniel Gutman

In the index: Waraira Repano National Park (Photo courtesy of Inparques)