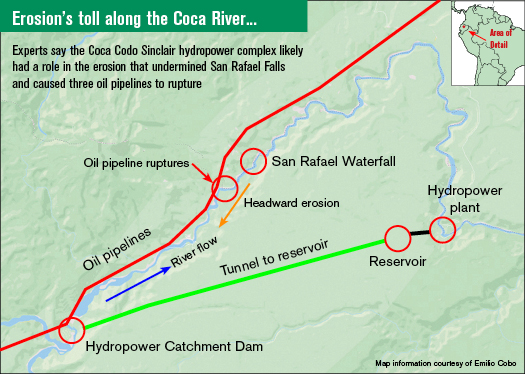

Erosion's toll along the Coca River. (Map information courtesy of Emilio Cobo)

First, Ecuador’s largest waterfall vanished. On Feb. 2 of this year, erosion on the Coca River in the country’s Amazon region created a huge sinkhole, largely erasing the country’s prized, 150-meter-high San Rafael Falls.

Then, on April 7, erosion 1.5 kilometers (0.9 miles) further upstream opened another sinkhole and broke three oil pipelines—including the two main conduits of Ecuadorian crude from Amazon-basin wellheads to terminals on the Pacific coast. In one of the worst Amazon region oil spills in decades, over 15,000 barrels (630,000 gallons) of crude escaped, causing severe downstream pollution in communities along the Coca and Napo Rivers.

Experts in Ecuador and abroad suggest the two events are related to a phenomenon known as hungry waters, in which rivers become more erosive after losing waterborne sediment. They say the cause in this case could be manmade—namely, Coca Codo Sinclair, a 1,500-megawatt, Chinese-financed hydroelectric complex on the Coca River that was inaugurated amid great fanfare in 2016. Coca Codo Sinclair was controversial from the start, in part due to its location in a geological fault zone near Reventador, one of Ecuador’s most active volcanoes. Experts also warned it might alter the Coca’s fluvial dynamics, a process some see as a factor in the oil-pipeline ruptures and the demise of San Rafael Falls.

Catchment dam in spotlight

The focus of this concern is the complex’s catchment dam, 17.5 kilometers (10.9 miles) upstream of the site of the pipeline breaks. The dam shunts some of the Coca’s flow to a nearly 25-kilometer (15-mile) tunnel, which bypasses a large river bend as it delivers water to the downstream reservoir and hydropower plant.

Critics argue that after the dam effectively forces the river to shed a portion of its sediment load, largely by slowing its flow, the clearer water released into the natural river channel below the dam behaves differently. Unburdened by suspended material, this “sediment-starved” or “hungry” water, experts say, can possess far greater erosive capacity, powerfully affecting the river’s geomorphology. Indeed, a recent study by the National Polytechnic School of Ecuador estimates the catchment dam boosted the river’s erosion rate by 42%. The study says the headward, or upstream, erosion on the Coca River might be related to the dam “producing the phenomenon of hungry water.”

Emilio Cobo, water-program coordinator in South America for the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), agrees decreased sediment load is key. “The alterations this [catchment dam] has caused to fluvial dynamics translate mainly into a loss of flow [and] interruption of the natural sediment load,” Cobo says. “The dam acts as a barrier.”

Coca Codo Sinclair was inaugurated in November 2016 in a showcase event involving Rafael Correa, Ecuador’s president at the time, and Chinese President Xi Jinping. Now, the complex is being criticized as a threat to natural and built resources. Such criticism, kindled by the collapse of San Rafael Falls, intensified after the rupture of three pipelines—the state-owned Trans-Ecuadorian Oil Pipeline System (SOTE) and the private OCP Ecuador, which carry crude, and an oil-byproducts line.

Downstream impacts

The spill affected 105 Coca and Napo River communities where 135,000 people live, says the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of the Ecuadorian Amazon (Confeniae), a large association of indigenous groups. There were reports that after flowing from the Coca into the Napo, contaminants may have reached Peru. “A slick was not observed moving into Peru, but communities [there] are talking about the water’s smell, changes in the river’s morphological conditions and declining fish stocks,” says attorney María Espinosa of Amazon Frontlines, a U.S.-based nonprofit that works to support indigenous rights.

Carlos Jipa, president of the Federation of Communes Union of Natives of the Ecuadorian Amazon (Fcunae), an association of over 100 Quechua communities, says the spill polluted “the river and fish, [and] the animals that live nearby, such as guantas [Cuniculus paca].”

Geologist and river specialist Isabel Carolina Bernal, a National Polytechnic School faculty member, warns headward erosion will continue taking a toll on the Coca. She and other experts believe the phenomenon poses medium-term risks to infrastructure, including the catchment dam and a portion of the highway linking Ecuador’s capital of Quito with the country’s oil-producing region of Lago Agrio.

Bernal recommends research to better understand the dam’s effects on the river. Cobo urges analysis of the environmental review and decision-making that led to construction of the dam. Advocacy groups, meanwhile, are calling on the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights to monitor the government’s response to the oil-pipeline collapse. And on May 16, Ecuador’s Constitutional Court began hearing a request by indigenous communities that the entities responsible for the oil pipelines be ordered to remediate damage from April’s spill and take steps to prevent future accidents.

- Mercedes Alvaro

In the Index: Broken oil pipelines dangle over Coca River sinkhole. (Photo by Petroecuador)